Degeneracy of the Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

Note: This post uses MathJax for rendering, so I would recommend going to the site for the best experience.

I just love being able to find neat ways to solve problems. In particular, there’s something about a combinatorial problem that is so satisfying when solved. The problem may initially look difficult, but a slight shift in perspective can bring the solution right into focus. This is the case with this problem, which is why I’m sharing it with you today. Don’t worry if you don’t know any of the quantum mechanics that goes in here. The ingredients themselves aren’t important to the solution of the problem.

Energy of the quantum harmonic oscillator

If you have taken a quantum mechanics class, there’s a good chance you studied this system. The quantum harmonic oscillator is one that can be solved exactly, and allows one to learn some interesting properties about quantum mechanical systems. Briefly, the idea is that the system has a potential that is proportional to the position squared (like a regular oscillator). In the quantum mechanical case, the aspect we often seek to find are the energy levels of the system. This is what is of interest in our problem here.

In one dimension, the energy is given by the relation $E_n = \left(n+1/2 \right) \hbar \omega$, where n is an integer greater or equal to zero, and the terms outside of the parentheses are constant (Planck’s constant and the angular frequency, respectively). However, what’s nice is that this extends into any number of dimensions in a straightforward way. If we want to look at the harmonic oscillator in three dimensions, the energy is then given by:

\[E_{n_x,n_y,n_z} = \left(n_x + n_y + n_z +3/2 \right) \hbar \omega.\]

In other words, there’s a n value for each dimension. We can even consider the harmonic oscillator in N dimensions, and the energy would change in the same way. We would just add a new n index, and throw in an extra factor of 1/2. Furthermore, it’s important to know that each combination of n’s gives a different physical system.

What you might notice from the three dimensional case is that there are different combinations of nx, ny, and nz that give rise to the same total energy. For example, we can note that the combinations (1,0,0), (0,1,0), and (0,0,1) all give the same total energy. This is called degeneracy, and it means that a system can be in multiple, distinct states (which are denoted by those integers) but yield the same energy. In this essay, we are interested in finding the number of degenerate states of the system.

The counting problem

Here’s the question. Given a certain value of n (which in the three-dimensional case is n = nx + ny + nz), how many different combinations of those three numbers can you make to get the same energy? If we want to be more general, for a given n and N (the number of dimensions), what is the degeneracy?

If we do a few examples, we will see that the degeneracy in three dimensions is one (no degeneracy) for n = 0, three for n = 1, six for n = 2, and ten for n = 3.

I don’t know if you’re seeing a pattern here, but it’s not super clear to me. I definitely don’t see how to generalize this to any n, let alone for more dimensions. As such, we’re going to look at this in a whole different way.

The method I’m going to discuss is one I found here, and is called the “stars and bars” method. It’s a beautiful technique that captures exactly what this problem is asking.

We start by thinking about how we can represent this problem. For a given n, we want to find a way to split this number into separate parts. Say we want to split the number into four parts. Then, we would need to introduce three splits in the number n so that there are four “pieces”.

How many parts do we want for our particular problem? Well, it depends on the dimension we’re working in! For example, if the dimension is three, we want to split n into three parts. This means we need to “cut” the number twice.

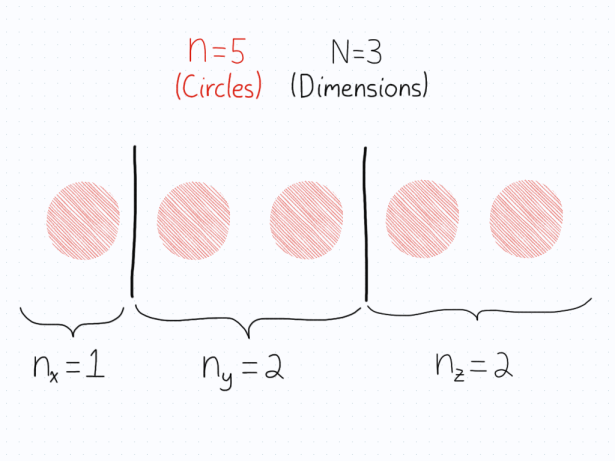

Words don’t describe this as well as an explicit visual example. Let’s pretend we have n = 5, and we are working in three dimensions. We will represent the number five by circles, and the splitting will be done using vertical bars. Then, here’s a way we can “cut” n.

As you can see, this is just another way to word our original question. What’s neat though is that the construction doesn’t actually “know” about the way the number n is being split. In other words, all we’ve done is introduce a second kind of object into the mix (the vertical bars). We recognize those vertical bars as dividing the number into three pieces, but the mathematics doesn’t care.

If you’ve taken some discrete mathematics, you may know where we’re going with this. We’ve reduced the question to finding the number of ways we can arrange objects. This is a common combinatorial problem, and one that is well-studied. The answer is ripe for the taking.

For our scenario, how many objects do we have in all? Well, there are n objects, and we have to also include the number of bars. But the number of bars is just N-1. Therefore, the total number of objects is N-1+n. Then, from those objects, we want to fix the position of the bars. Therefore, we get the usual combinations formula. If we want to label the degeneracy as gn, we get:

\[g_n = {N-1+n \choose N-1}.\]

In particular, we can now solve this question for three dimensions. Substituting N=3, we get:

\[g_n = {2+n \choose 2} = \frac{(2+n)!}{2! n!} =\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2} .\]

All I can say is that this is slick. I remember first trying to solve this on my own, and getting stuck. Even when I was given the answer, it didn’t feel satisfying to me. I knew that there had to be some better explanation for the degeneracy. I felt like there should be some combinatorial argument for the degeneracy, and it turned out that I was right! I hope that this argument helps clear things up for other students who were wondering about the formula and how to get it. In my mind, this is one of the clearest ways to get it.