Period of a Pendulum

The pendulum is a classic physical object that is modeled in many introductory physics courses. It’s a nice system to study because it is so simple, yet still allows students to see how to study the motion of a system. Here, I want to do through the steps of deriving what is usually seen as an elementary result, the period of a pendulum, and show how it is actually more complicated than what most students see.

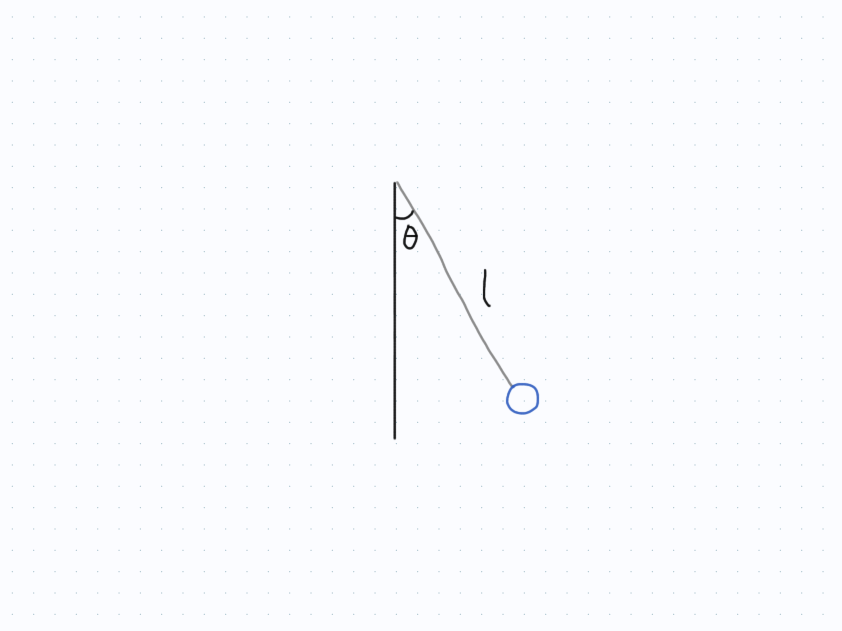

To begin with, what exactly is a pendulum? This may seem like an easy question, but it’s a good idea to have a well-defined system. So, the pendulum we will be looking at today is called a simple pendulum. Surprising no one, a simple pendulum is the most idealized pendulum, consisting of a point mass attached by rod of fixed length. This means we aren’t dealing with a pendulum that has a flexible rope that changes length, nor do we have something like a boat, which doesn’t quite act like a point mass since the mass is distributed throughout the object and isn’t localized. In other words, our situation should look something like this:

You may be wondering why we aren’t using Cartesian coordinates, and the reason is quite simple. In Cartesian coordinates, we would need to specify both the $x$ and $y$ coordinates, which requires two degrees of freedom and is also a pain in this particular setup. By contrast, using polar coordinates is more compact since the radius $r$ is fixed (in this case, $r=l$), which means we only have one degree of freedom, the angle $\theta$.

To begin our analysis, we will start with our generic equation for conservation of energy, which looks like this:

\[\begin{equation}

E = T + U.

\end{equation}\]

Here, the kinetic energy is $T$ and the potential energy is $U$. To know the kinetic energy, we need to know the magnitude of the velocity of the object, which we don’t know at the moment (and which changes depending on the angle $\theta$). We do know though that the kinetic energy is given by $T = \frac{1}{2} m v^2$, where $v$ is the magnitude of the velocity (the speed), so we will keep that to the side.

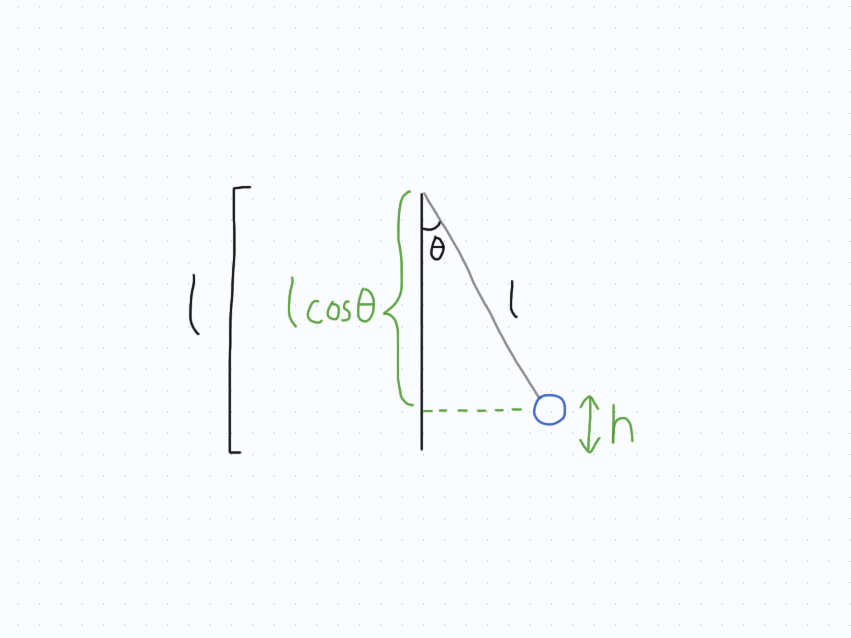

We also know that the potential energy is given by the familiar equation $U = mgh$ on Earth, where $h$ is the height of the object from the ground. To find this height $h$, we need to draw some clever lines and invoke some geometry:

From the diagram above, we can see that the height is given by $h = l \left( 1 - \cos \theta \right)$. Therefore, the potential energy is:

\[\begin{equation}

U = mgh = mgl \left( 1 - \cos \theta \right).

\end{equation}\]

With this, we almost have everything we need in our equation. The goal is to isolate for our speed $v$, so we can then integrate it over a whole cycle to find the period. To do this, let’s remember our conservation of energy equation: $E = T + U$. This equation states that the total energy $E$ is always a constant in time. In other words, $\frac{dE}{dt} = 0$, and so we can simply find the total energy at one particular instant, and then substitute it for $E$.

What we will do is consider the energy that the pendulum initially has, just before it is allowed to fall. At that moment, it has an initial angle which we will call $\theta_0$, and since it isn’t moving, the pendulum has no kinetic energy. Therefore, the energy of the pendulum is:

\[\begin{equation}

E = mgl \left( 1 - \cos \theta_0 \right).

\end{equation}\]

We can now make this equal to the sum of the kinetic and potential energy at any time to get:

\[\begin{equation}

mgl \left( 1 - \cos \theta_0 \right) = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 + mgl \left( 1 - \cos \theta \right).

\end{equation}\]

Since each term in this equation has the mass $m$ in it, we can see that our result will be independent of the mass. If we then isolate for $v^2$, we get:

\[\begin{equation} \label{vSquared}

v^2 = 2gl \left( \cos \theta - \cos \theta_0 \right).

\end{equation}\]

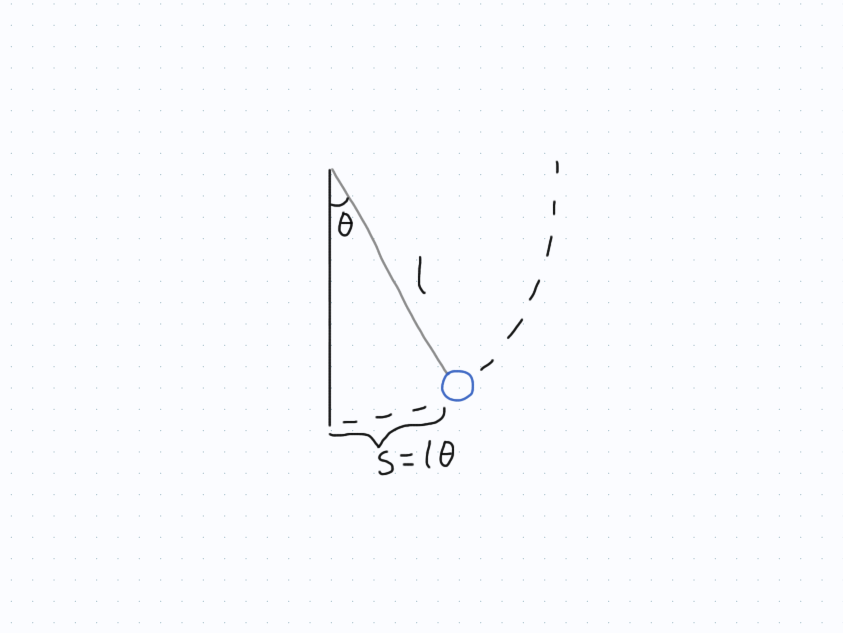

At this point, we need to think about what the speed $v$ is. The definition of speed is $v = \frac{ds}{dt}$, where $s$ is the path length. Fortunately, the path length of a pendulum is very easy to find, since it’s simply the arc length of a circle!

From the above diagram, we can see that the path length is given by $s = l \theta$. Therefore, the speed is:

\[\begin{equation}

v = \frac{ds}{dt} = l \frac{d\theta}{dt}.

\end{equation}\]

We can now substitute this into Equation \ref{vSquared}, and solve for $\frac{d\theta}{dt}$:

\[\begin{equation}

\frac{d\theta}{dt} = \sqrt{\frac{2g}{l}} \sqrt{\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0}.

\end{equation}\]

Note here that I’m only considering the positive solution for $\frac{d\theta}{dt}$, since we will be solving for the period, which is a positive quantity. What we will now do is employ the method of separation of variables to integrate this quantity. If you aren’t familiar with this method, I suggest taking a look at a resource on differential equations such as here. Separating our variables gives us:

\[\begin{equation}

dt = \sqrt{\frac{l}{2g}} \frac{d\theta}{\sqrt{\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0}}.

\end{equation}\]

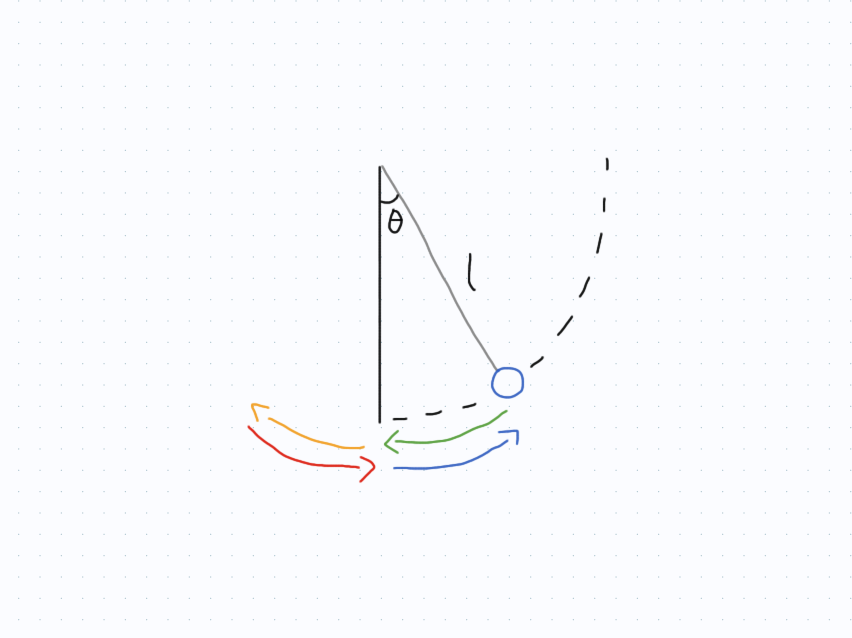

This is good. We now have an expression for $dt$, which means we can integrate it for the angle between $0$ and $\theta_0$, and this will be one quarter of the period. To see why it’s only a quarter of the period, look at the following sketch (each arrow is a quarter period):

Integrating gives us:

\[\begin{equation}

\sqrt{\frac{l}{2g}}\int_0^{\theta_0} \frac{d\theta}{\sqrt{\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0}} = \int_0^{T/4} dt = \frac{T}{4}.

\end{equation}\]

And solving for the period $T$ gives:

\[\begin{equation} \label{fullPeriod}

T = \sqrt{\frac{8l}{g}}\int_0^{\theta_0} \frac{d\theta}{\sqrt{\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0}}.

\end{equation}\]

This is the full expression for the period of a pendulum at any initial angle $\theta_0$. The only slight issue is that, while correct, this expression is not easily integrated. In fact, I don’t know how to integrate it at all. What we would like the period to be is of the form:

\[\begin{equation}

T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{l}{g}} + \ldots

\end{equation}\]

The expression above would be what is called a Taylor expansion, with the first term being what you might have already seen to be the period of a pendulum, plus some correction factors that are contained in the ellipsis. To get it into this form, we want to be able to use the binomial expansion, which is given by:

\[\begin{equation} \label{expansion}

\left( 1 + x \right)^n \equiv 1 + nx + \frac{n(n-1)}{2!}x^2 + \frac{n(n-1)(n-2)}{3!}x^3 + \ldots

\end{equation}\]

To do this, we need to transform Equation \ref{fullPeriod}. First, we will perform what may seem like a totally random substitution, but bear with me. We will change coordinates and go from $\theta \rightarrow \psi$. This mapping will be done using the following relation:

\[\begin{equation} \label{transform}

\sin \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) = \sin \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \sin \psi.

\end{equation}\]

Looking at this relation, we can see that when $\theta$ ranges from 0 to $\theta_0$, the corresponding variable $\psi$ varies from $0$ to $\pi / 2$.

Implicitly differentiating each side gives us:

\[\begin{equation} \label{dTheta}

\frac{1}{2} \cos \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) d\theta = \sin \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \cos \psi \ d\psi.

\end{equation}\]

We can then pull out a handy trigonometric identity called the double angle identity, which is given by:

\[\begin{equation}

\cos \left( 2\theta \right) = 1 - 2\sin^2 \theta \rightarrow \cos \theta = 1 - 2\sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right).

\end{equation}\]

Using this identity, we can rewrite the expression inside the square root of Equation \ref{fullPeriod} as:

\[\begin{equation}

\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0 = 1 - 2\sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) - \left( 1 - 2\sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \right) \\

= 2 \left( \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) - \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) \right).

\end{equation}\]

From here, we can insert our original substitution from Equation \ref{transform} into the second term above, giving us:

\[\begin{equation}

2 \left( \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) - \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) \right) = 2 \left( \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) - \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \sin^2 \psi \right) \\

= 2 \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \left( 1 - \sin^2 \psi \right) \\

= 2 \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \cos^2 \psi.

\end{equation}\]

Just to note, from the second to third line, I simply used the Pythagorean theorem. Now, since we wanted the square root of $\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0$, we can take the square root of the above expression. Furthermore, we can use Equation \ref{dTheta} in order to find an expression for $d \theta$:

\[\begin{equation}

d\theta = \frac{2\sin \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \cos \psi \ d\psi}{ \cos \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right)}.

\end{equation}\]

From this, we can insert everything into the integral of Equation \ref{fullPeriod} and simplify. Note here that I’ve omitted the prefactor in the front of the integral just to get things a little cleaner, but we won’t forget about it.

\[\begin{equation}

\int_0^{\theta_0} \frac{d\theta}{\sqrt{\cos \theta - \cos \theta_0}} = \int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{2\sin \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \cos \psi \ d\psi}{ \cos \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) \sqrt{2} \sin \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \cos \psi} \\

= \sqrt{2} \int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{d\psi}{\cos \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right)}.

\end{equation}\]

We’re almost there. Now, we can simply used a rearranged version of the Pythagorean theorem to write:

\[\begin{equation}

\cos \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right) = \sqrt{1 - \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta}{2} \right)} = \sqrt{1 - \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \sin^2 \psi}.

\end{equation}\]

Here, I’ve made use of equation (13) again in order to write this expression in terms of $\psi$. Throwing this all together and reintroducing the prefactor in front for the period gives us the following result for the period:

\[\begin{equation} \label{Period}

T = 4 \sqrt{\frac{l}{g}} \int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{d\psi}{\sqrt{1 - \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) \sin^2 \psi}}.

\end{equation}\]

I don’t know about you, but that was a lot of work. This integral is actually a special kind of integral. It’s called a complete elliptic integral of the first kind, and is defined by:

\[\begin{equation}

k(m) = \int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{d\psi}{\sqrt{1 - m\sin^2 \psi}}, \ \ \ 0 \le m \le 1.

\end{equation}\]

In our case, $m = \sin^2 \left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right)$. What’s nice about this form of the integral is that it is indeed in binomial form, so we can expand it. We therefore have:

\[\begin{equation} \label{long}

\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - m\sin^2 \psi}} = 1 + \frac{1}{2}m\sin^2\psi \\ + \frac{ \left( \frac{-1}{2} \right) \left( \frac{-3}{2} \right)m^2\sin^4\psi}{2} + \frac{ \left( \frac{-1}{2} \right) \left( \frac{-3}{2} \right) \left( \frac{-5}{2} \right) \left(-m^3\sin^6\psi \right)}{3!} \\ + \frac{ \left( \frac{-1}{2} \right) \left( \frac{-3}{2} \right) \left( \frac{-5}{2} \right) \left( \frac{-7}{2} \right) m^4\sin^8\psi}{4!} + \ldots \\ = 1 + \frac{1}{2}m\sin^2\psi + \left( \frac{1 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 4} \right)m^2\sin^4\psi + \left( \frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6} \right)m^3\sin^6\psi \\ + \left( \frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6 \cdot 8} \right)m^4\sin^8\psi + \ldots

\end{equation}\]

This looks like quite the jumbled expression, but we can can write it quite succinctly in the following form:

\[\begin{equation}

\left( 1 - m\sin^2\psi \right)^{-1/2} = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!} m^n \sin^{2n}\psi.

\end{equation}\]

Here, the double factorial sign (!!) means that we skip a number each time we do the multiplication. Therefore, $5!! = 5 \cdot 3 \cdot 1$ and $6!! = 6 \cdot 4 \cdot 2$. You can verify that this does represent the above expression of Equation \ref{long}. We are now in a better position to evaluate the integral. It looks like this:

\[\begin{equation} \label{sum}

\int_0^{\pi/2} \frac{d\psi}{\sqrt{1 - m\sin^2 \psi}} = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!} m^n \int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2n}\psi \ d\psi.

\end{equation}\]

This last integral is a bit of tricky one, but we will show that the integral is given by:

\[\begin{equation} \label{In}

\int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2n}\psi \ d\psi = \frac{(2n - 1)!!}{(2n)!!} \cdot \frac{\pi}{2}.

\end{equation}\]

To get this result, we will use recursion. First, we note that the values of $n$ are all positive, which is clear from Equation \ref{sum}. This means our lowest value of $n$ will be one. If we label the integral in Equation \ref{In} as $I(n)$, then we can evaulate this function to get:

\[\begin{equation}

I(1) = \int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2}\psi \ d\psi = \frac{\pi}{4}.

\end{equation}\]

With the base case out of the way, we now tackle the whole integral. Let’s start by splitting up the integral as such:

\[\begin{equation}

\int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2n}\psi \ d\psi = \int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2n-1}\psi \sin \psi \ d\psi.

\end{equation}\]

We can now use integration by parts to partially evaluate this integral. If we use $u = \sin^{2n-1} \psi$ and $dv = \sin \psi$, we get:

\[\begin{equation}

\int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2n}\psi \ d\psi = -\cos \psi \sin^{2n-1} \psi \left. \right\rvert_0^{\pi/2} + (2n-1) \int_0^{\pi/2} \cos^2\psi \sin^{2n-2}\psi \ d\psi.

\end{equation}\]

The first term evaluates to zero, and so we are only left with the integral. We can then change the cosine into a sine and rearrange things to give:

\[\begin{equation}

(2n-1) \int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2(n-1)}\psi - \sin^{2n}\psi \ d\psi.

\end{equation}\]

If you look at this and compare it to our definition of $I(n)$ from Equation \ref{In}, you’ll notice that we can write the above equation as:

\[\begin{equation}

I(n) = (2n-1) \left[I(n-1) - I(n) \right].

\end{equation}\]

Solving for $I(n)$ gives:

\[\begin{equation}

I(n) = \left( \frac{2n-1}{2n} \right) I(n-1).

\end{equation}\]

This is a recurrence relation, which means it tells us how to construct the next term from the previous one, as long as we have a beginning “seed”. Thankfully, we do have one, which is $I(1) = \pi/4$.

What we want to do at this point is to keep on applying the recurrence relation to the term $I(n-1)$, until we get all the way to $I(1)$, where we stop. I’ll illustrate a few of these for you, and hopefully it becomes clear what the pattern is.

\[\begin{equation}

I(n) =\left( \frac{2n-1}{2n} \right) I(n-1) \\

= \left( \frac{2n-1}{2n} \right)\left( \frac{2(n-1)-1}{2(n-1)} \right) I(n-2) \\

= \left( \frac{2n-1}{2n} \right)\left( \frac{2(n-1)-1}{2(n-1)} \right) \left( \frac{2(n-2)-1}{2(n-2)} \right) I(n-3).

\end{equation}\]

I could continue, but this is a good representation of what happens. In summary, the numerators of the fractions are odd numbers (since they are in the form $2k+1$), and the denominators are even numbers (since they are in the form $2k$). Furthermore, as you go down the fraction, you go from an odd number to the next closest odd number, and the argument is the same for the even numbers. Therefore, what we are really doing is another factorial all the way until we get to $I(1)$, which we can evaluate since it is our starting seed. Therefore, we get:

\[\begin{equation}

I(n) = \frac{(2n-1)!!}{2n!!} \left( \frac{\pi}{2} \right).

\end{equation}\]

Now that we have this result, we can put it all together to give us:

\[\begin{equation}

\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!} m^n \int_0^{\pi/2} \sin^{2n}\psi \ d\psi = \frac{\pi}{2} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \left[\frac{(2n-1)!!}{(2n)!!}\right]^2 m^n.

\end{equation}\]

Expanding this gives us the following infinite series:

\[\begin{equation}

\frac{\pi}{2} \left[ 1 + \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^2m + \left( \frac{1 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 4} \right)^2m^2 + \left( \frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6} \right)^2m^3 + \ldots \right]

\end{equation}\]

If we recall that $m = \sin^2\left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right)$ and we insert the prefactors for the period from Equation \ref{Period} in, we get the following result for the period of the pendulum:

\[\begin{equation} \label{Final}

T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{l}{g}} \left[ 1 + \frac{1}{4}\sin^2\left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) + \frac{9}{64}\sin^4\left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) + \frac{25}{256}\sin^6\left( \frac{\theta_0}{2} \right) + \ldots \right]

\end{equation}\]

This is the full expression for the period of the pendulum with any starting angle $\theta_0$. What’s quite nice about this expression is that we can immediately see that if $\theta_0 \approx 0$, then all of the sine functions become very close to zero and so the only important term in the square brackets is the one. At this point, the period becomes what one usually learns (for small angles): $T = 2\pi \sqrt{\frac{l}{g}}$.

Furthermore, we can see that when our initial angle gets bigger, it becomes more important to take on successive terms within the brackets of Equation \ref{Final}.

Hopefully, this wasn’t too bad. I wanted to go through the calculation as explicitly as possible, since I remember being a bit confused when I saw it for the first time. As such, I want to make sure things are illustrated nice and slow so everyone can follow.

What I love the most about these long analytical expressions is how you can recover the simpler result you had from simplifying the problem. We can easily see that our “usual” period is nestled within the long infinite expression. Lastly, I just wanted to make clear that one assumption we did make was that we were dealing with a point mass pendulum. In other words, we still weren’t quite modelling a physical pendulum, which requires taking into account the centre of mass of the bob and the rod of the pendulum together. Still, this is enough precision for today, so we will leave it at that.