The Limitations of Models

As many students in the sciences know, the reason we use mathematics to describe our results is because mathematics is the most precise language we possess. It’s not like we have some sort of favouritism towards mathematics that we don’t have to other languages like English or French. Quite frankly, it’s an issue of precision in what one is communicating. It’s the difference between saying I can see a red light and that I can see a light of about 600 nanometres. It’s the difference between basing a prediction on past results and basing on extrapolating from a model.

However, what is often missed in the public is the fact that science is based on mathematical models. And, as any scientist will tell you, a model is only as good as the assumptions it makes. This means the models are inherently different from what we would call “real life”.

Simplicity to complexity

When you first learn physics in secondary school, you typically learn about the big picture concepts, such as Newton’s laws, some optics, and maybe even something about waves. If we focus on only Newton’s famous $\vec{F} = m \vec{a}$, you learn about solving this equation for an easy system. Additionally, one usually starts without any notion of calculus, so the questions revolve around either finding a force or finding the acceleration of the system. Personally, I remember analyzing systems such as a block that is subject to a variety of constant forces. This made the analysis easy, compared to what one does a few years later in more advanced classes.

However, what one must keep in mind is that the systems I was analyzing weren’t realistic. If one stops to think about it, there aren’t many forces that are constant with time (even our favourite gravitational force $m\vec{g}$ isn’t technically a constant). However, we weren’t going to be thrown to the lions in our first physics class, so these simple systems were enough to begin.

Years later, I would refine these models to become gradually more realistic. To give an explicit example, consider the equations for kinematics, which one learns about in secondary school and are given by:

\(\begin{align}

x(t) = x_0 + v_0 t + \frac{1}{2}at^2,\\

x(t) = \left( \frac{v + v_0}{2} \right) t,\\

v(t) = v_0 + at,\\

v^2 = v_0^2 + 2a\left(x - x_0 \right).

\end{align}\)

What one immediately learns following this is that these are equations that describe the motion of a free-falling object under a constant acceleration. These two emphasized terms are important, because unless you’re trying to describe the motion of projectiles in outer space, these equations don’t actually describe the motion of the systems. There are a few reasons why this is so. First, as alluded to above, these equations are only valid where there is no force acting on the system except for gravity. This is obviously not realistic, since there are other forces that can act on a system when they are launched (such as air friction). Therefore, modeling the situation as if air friction didn’t exist can only give an approximate answer at best. The presence of only gravity as a force is what is meant bu the term free-falling.

Second, the acceleration needs to be constant, and this isn’t true either. If we simply take the example of launching a system into the air, the fact that air friction acts as a force on the system changes the acceleration of the system, thereby nullifying our kinematic equations once again.

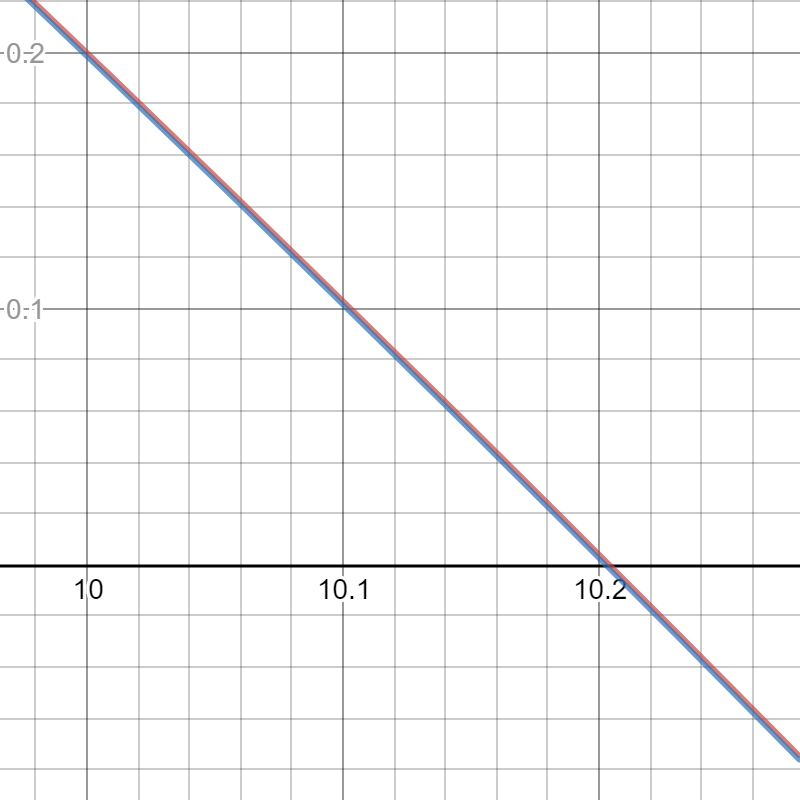

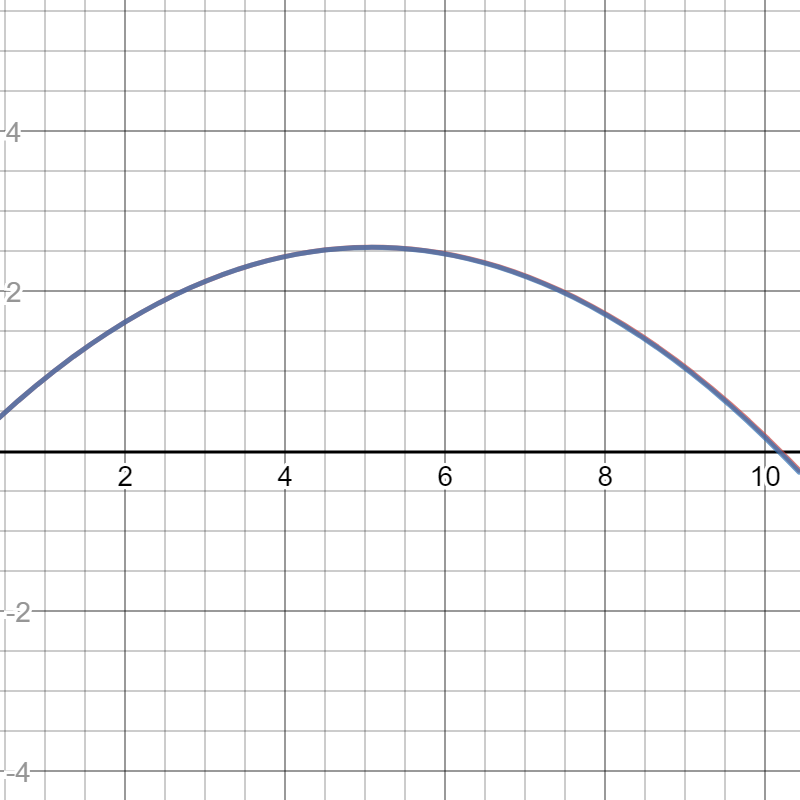

Alright, so those are a few reasons why the kinematic equations don’t work, but what does the difference look like in our models? I won’t go through the whole derivation of the kinematic equations when we add in air friction, but here’s a plot that shows the difference between the two for a tennis ball.

As you can see, the difference is very small. Indeed, it took me a bit of time to figure out what kind of object would show some more obvious deviations from the original parabola (which is the red curve). Finally, I found a good example, which is a table tennis ball. The more accurate curve that takes air friction into account (in blue) is quite close to the red curve, so to a first approximation, our original model without air friction is pretty good. Actually, if you take the whole trajectory into account, you can see that the two curves diverge in the latter half of the trajectory.

You might be thinking, “Alright great, we have the solution for the trajectory, so now this problem is solved.” But that’s not quite true. If you’ve ever thrown hit a table tennis ball, you know that it doesn’t just fly in the air in one position. It spins, and that rotation changes how the ball moves (as anyone who plays table tennis knows). As such, the moral of the story is that we can always add more elements into the models that make them more accurate. However, that always comes at the cost of simplicity, so your model becomes more difficult to compute as you increase the features it encodes. At some point, you have to choose where you want to fall on the spectrum of simplicity to complexity.

How much stock can we put into models?

So who cares about the trajectory of a ball when we throw it? Chances are, not many. The reason I wanted to show you this one was just to illustrate what we need to take into account when we want to model some sort of phenomena. There are always tradeoffs, and these tradeoffs affect our accuracy.

The problem that we as scientists can fall into is failing to communicate how these models work to the public. It’s nice to give big, qualitative statements about the future, but often we don’t share the limitations of these statements. What I mean by this is simply that our statements in science are often predicated on models. And, as I mentioned in the beginning of this piece, models are only as good as their built-in assumptions. Einstein’s theory of general relativity is a fantastic framework for understanding and predicting many features of spacetime, but if we suddenly see that there isn’t a speed barrier in the universe, then the whole model is useless physically. That’s obviously an extreme example, but the broader point is to keep in mind the limitations of models.

A model is something we use to describe the world. If it’s a very good model, then it may even make predictions about things we haven’t yet discovered. But what you shouldn’t do is keep yourself tied to a specific model. That’s because every model has its own domain of applicability, and trying to apply the model past this domain isn’t a good idea.

We should all keep this in mind when we hear news reports about extraordinary things. First, what kind of model is being used? Is it a model that has proven value, or is it something completely new? Second, what kind of domain of applicability does this model have, and does going past it significantly change the results? As you can see from the example we did above, not including air friction didn’t significantly change the results. However, the amount that is “bad” is very subjective, which means it depends on the application. If we are trying to understand simple models of astrophysical phenomena, we might not be too picky if our results could be up to 20% off (depending of course on the situation). However, if you have a model that predicts certain health issues in patients, misidentifying one in five patients is much too high (for myself).

Therefore, the next time that we hear something extraordinary on the news, think about the model that’s being used. I understand that we can’t possibly research every single ridiculous claim that is made, but a bit more skepticism and curiosity about the details of such claims would not be a bad thing.