To be a scientist means to explore. You need to start from what is known and jump out into the void, investigating new ideas. In this regard, the scientist is an explorer, a person searching for new truths in a world without a map. To be more precise, a scientist uncovers the new map as they learn.

When we talk about science, we like to emphasize the new discoveries. Whether that’s the discovery of gravitational waves, a breakthrough in gene-editing, or advances in machine learning, scientists get excited when a new truth about the world is unearthed.

In fact, I would argue that it’s the joy of discovery which drives a lot of scientists. It’s the chase for something new and unknown that excites them. So, if a scientist discovers a new pathway to superconductivity, they will be excited, but only until the next project. Then, the previous discovery is all but a nostalgic memory.

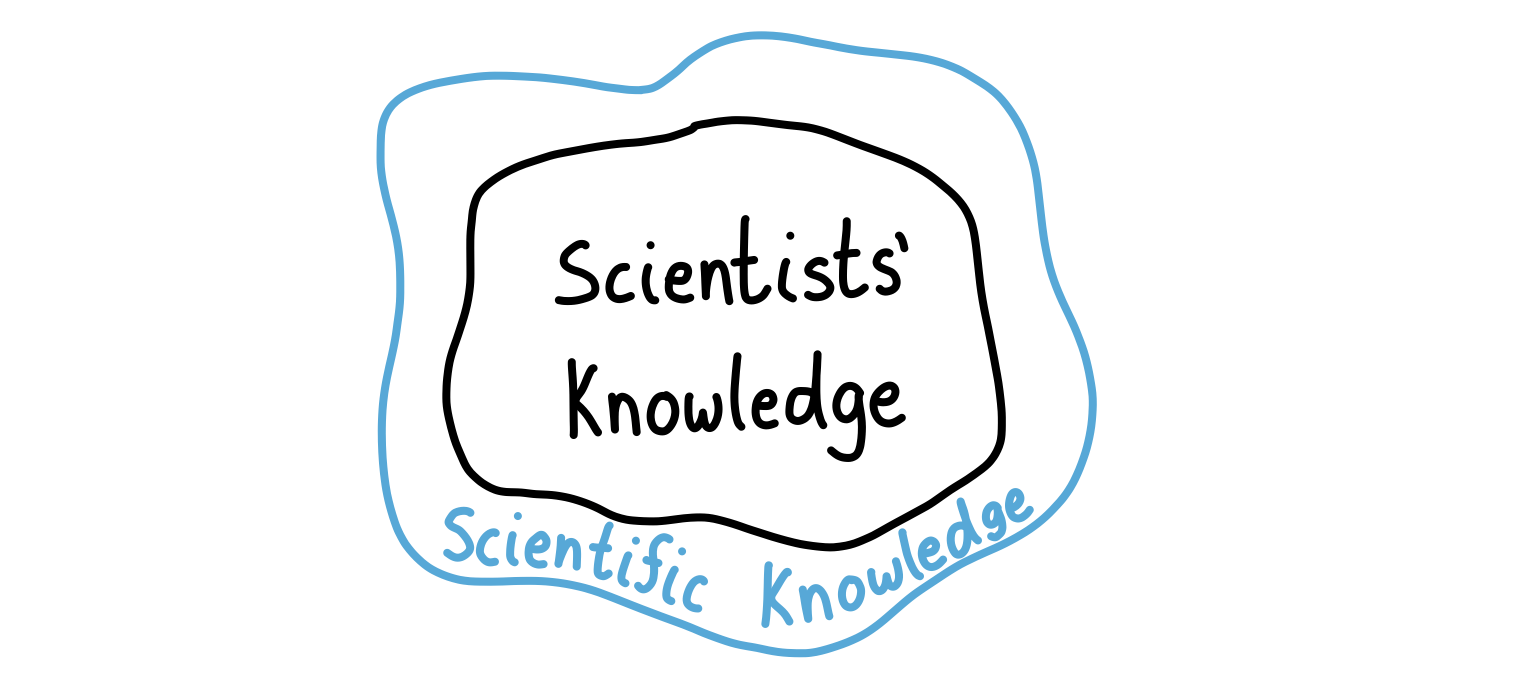

We could imagine humanity’s scientific knowledge as some sort of uneven boundary:

It’s uneven because some areas of knowledge have advanced more quickly than others. If I were to animate the boundary, it would expand, but not uniformly. It would resemble something closer to a bubble in the midst of formation, its surface undulating.

I like this metaphor because the bubble’s surface is what scientists are working on expanding. We want our horizon to reach further, and so to do this, we push on the surface of the bubble. This is what doing research looks like:

The goal of scientists is to push on this boundary as much as possible.

But there’s actually another bubble, and its nestled inside of the first. This bubble is what I would call “scientists’ knowledge”.

You might be wondering what the difference is between the two. The difference is that the inner bubble refers to the knowledge of scientists, while the outer one refers to the knowledge of science. The inner bubble is tied to humans, while the outer one is a product of humans.

Depending on your awareness of the scientific literature, the following may come as a shock: It’s messy.

We might like to think that the scientific literature is a nice, curated space with everything neatly organized and filed away properly, but that’s woefully optimistic. Instead, I think of the scientific literature more like a student’s messy desk, with papers and books all over the place. Finding things can either be super easy or downright impossible.

It’s true that a lot of the material is organized, but what I fear though is the fracturing of nearby scientific fields. If everyone is working in their own “mini sphere” of science, then it can be difficult to propagate a discovery from one part of the boundary to another (let alone in different fields!). This suggests researchers will “waste time” coming up with ideas that other scientists have already discovered, but haven’t reached their field yet.

Plus, if scientists could know this information, than chances are they could make new connections and generate new knowledge. This is what the inner bubble is referencing. We have a lot of scientific knowledge, but at any one time, we aren’t necessarily aware of it all. So while our potential is the blue boundary, our current reality is the black one.

That’s one problem. There’s another one though: As time goes on, the horizons of the field (the outer bubble) gets further and further away. This has led me to joke that there will eventually be an “event horizon” of sorts where a new scientist won’t be able to contribute to science because the boundary is further away than they can ever get to within their lifetime.

Fortunately, we have one way to manage this: Education. By training budding youngsters in school, we are able to give them a fast ride to a place much closer to the boundary of the bubble.

But this gap between where you end up after your education and where you want to go as a scientist is difficult to traverse. The main reason is that the resources available dwindle to none as you make your way to the boundary (See Reference 1). That’s to be expected. After all, there are fewer people there! The problem though is that the burden for creating resources falls on the experts, the ones who are already at the bubble’s boundary. But many of them don’t want to spend time on this. Instead, they are drawn to the next adventure. What they leave behind is then a relic of their progress, but it’s often rough, and left to others to make sense of it.

It’s this roughness that concerns me as a scientist. If we want to ensure steady progress in science, we need to make sure people are able to get to the boundary. Unfortunately, few take the time to put all of the work together into one big piece that summarizes what has been done.

In essence, we’re all poking at the bubble around the same reason, unaware (or at least, not fully understanding of) the other work that has been done.

To fix this, I want to propose an entirely new class of scientist. Currently, being a scientist is more or less synonymous with being a researcher. That’s fine, but I think the accumulation of scientific knowledge is going to force us to develop another type of scientist.

If the traditional scientist is an explorer, then this new type of scientist is an absorber.

Absorbers

What does an absorber do, and how do they contribute to science?

An absorber is someone who isn’t satisfied with the state of our scientific knowledge. In particular, they feel like there are too many papers and not enough synthesis of ideas. If everyone goes in their own direction, we might make some progress, but imagine how much more we could make if we made a more directed effort as a collective. This is the motivation of the absorber.

To get there, an absorber isn’t driven by discovering new things. Instead, they are driven by understanding the knowledge we have now. On its head, this sounds kind of silly. If someone has figured out a result, then surely we understand it? While that’s true to a certain degree, the absorber sees the opportunity in connecting that result to others. Remember, the fields we have in science are a human construct to aid categorization. In reality, things are much more connected and entangled than we give them credit for. An absorber sees this as an opportunity for generating new knowledge from the knowledge we have already.

But more than this, an absorber seeks to understand a field and its material. This is the crucial difference between an explorer and an absorber. Once the explorer discovers something, they move on to the next thing. The absorber is the one that makes the second pass on the material the explorer has moved on from and synthesizes it so that others can come along and get up to speed more quickly.

This benefits scientists in two ways:

First, it makes getting to the boundary of scientific knowledge easier. If an absorber spends time really understanding something, they are able to write about it, producing the resources necessary for the next generation of explorers to march towards the boundary. This would relieve the issue of not having enough resources near the boundary. An absorber’s main job would be taking these discoveries, absorbing them, and then sharing that understanding to the wider scientific community.

Second, humanity’s knowledge of the scientific literature grows as a result of having absorbers. That’s because of the simple fact that the scientific literature isn’t composed of neatly-stacked rows of books and information, but is more a pêle-mêle of observations, anecdotes, and curiosities. By having absorbers whose job is to comb through the literature, understand large swaths of it, and share that knowledge to other scientists, the possibility for discovery among the ideas we already know grows.

Just think about this tantalizing possibility: How many scientific insights are hiding within the literature right now, simply waiting for someone to come across two disparate pieces of information and connect the dots? My guess is that there are many such discoveries waiting to happen, and an absorber would be primed for helping make them.

The status of an absorber

To take this idea of a second type of scientist seriously, there needs to be some incentive structure for them. We give grants to explorers to uncover new insights, but what can we do to incentivize the absorber?

Here, I want to connect another problem in science that an absorber could solve: peer review. Simply put, peer review in science has lots of problems, the first of which is that scientists do this on a more-or-less volunteer basis (see Reference 2). That’s workable, but it does introduce plenty of work for scientists who are really explorers. They don’t want to spend time reviewing papers when the next discovery could be made.

An absorber, on the other hand, would be the perfect person for the job. Because their role is to read a lot of the scientific literature and understand the cutting-edge science on a deep level, they would be well-suited for reviewing papers. An absorber knows the work that has been done before, and can situate the space the new work fills.

This is how I imagine a lot of the funding for an absorber would come from. They would be (mainly) paid as professional peer reviewers, and this would allow them to spend time absorbing the material of a field.

To be clear, an absorber is a very different type of scientist than an explorer. Both deserve to be called scientists. I’m arguing that we need to let go of the notion that a scientist will be both a master absorber and explorer. As our bubble of scientific knowledge grows, it becomes more difficult to wrap your head around even a small bit of the literature while still making discoveries. Absorbers would relieve this burden.

I think it would take time for the status of an absorber to match that of an explorer. But it’s crucial that we don’t shovel people we think “aren’t good enough” to be an explorer into an absorber role. That would be the wrong approach. I envision it as something quite different. If you’re set on being an explorer and it turns out that the career doesn’t work out, being an absorber is not a “fall back” option. Instead, it’s an entirely different track.

That being said, I still think there are some scientists who could do both. But professionally, this distinction highlights the growing needs of scientists in an age where the amount of stuff we know is expanding at a lightning-fast rate.

My vision of an absorber is a cross between a librarian and a teacher. An absorber is a librarian in the sense that they will have a good idea of the work being done in a specific research field. If you come to them and ask for recommendations on what to read, they will be able to give you several directions to start.

An absorber is a teacher in the sense that they are able to explain and teach the main ideas of cutting-edge research to others who want to learn. This requires the difficult work of reading a paper, understanding the new ideas, and then explaining them to others in a pedagogical way. The word “pedagogical” is crucial here. If we want an absorber to succeed as a teacher, they need to transform the rough insights of an explorer into steps for the curious learner to follow.

For this latter part, I think tools other than the PDF/paper will be necessary. To be concrete, I’m thinking of examples like Distill, which focuses on machine learning research and explains it using web technologies that really allow the curious individual to grasp the concepts.

An absorber would be well-versed in programming/designing these experiences. Whether it’s in a Jupyter or Colab notebook, whether it’s using animation software like manim, or whether it’s using hand-drawn sketches and words (this is more old-school, like I use here), the goal is to facilitate sharing research ideas to those looking to learn.

I do have a bias here: As a PhD student, I feel this chasm between the resources found in textbooks for “established” ideas and the lack of resources for anything else. But I don’t think that graduate students are the only people who would benefit from this. Heck, how are we supposed to encourage explorers to be interdisciplinary if they can’t easily jump from one boundary to another? Sure, there’s a need to know the fundamentals, but I think we also have to acknowledge that educational resources on the cutting-edge are lacking.

Does anyone really want to be an absorber?

And here’s the question that matters. If nobody is interested in becoming an absorber, then this idea is a non-starter.

I don’t know if it’s clear from reading this (and the rest of my essays), but being an absorber is something I can get behind. Being an explorer is great, but explaining research in a clear way is an art and a skill. One that I’m always working on.

I also think having these separate roles would help build scientific groups that have a variety of expertise. From my experience, collaboration is the way science is done now. As such, a group can really benefit from having people with specialized skillsets.

Where would we get the funding for this whole new type of scientist? I don’t know. At some level, it would take away from the funding given to explorers. But I think time is only going to make this a more pressing need: The literature is growing so fast that in order to “master” a field, you need to define it more and more narrowly. This means an expert won’t know X, but a sub-sub-sub-sub-component of X. What an absorber would do is bring a higher-level perspective to a scientific community, lightening the load that explorers must shoulder now.

Science is changing. There are more scientists than ever before, and we are all poking at the boundary of scientific knowledge. To make sure we do it in a way that allows us to retain that knowledge (and not have it be buried in the literature), absorbers would be the main players to read the literature, understand things, and then help point the explorers in a promising direction.

Plus, absorbers would take the role of teachers of the cutting-edge. Using our best tools available, they would bring the insights of explorers to the other scientists, giving everyone a boost towards the boundary.

And finally, absorbers would be the new gatekeepers in peer review. Instead of relying on explorers acting on a sense of duty, absorbers would take on the task of peer review, since this will help them build up a sense of a field at the same time.

My proposal here is only a rough view of what could work. The point isn’t to follow this idea exactly. Instead, it’s about highlighting a broader truth: Contributing to science doesn’t have to only be done by explorers. Instead, there’s a large role to be played by the absorbers, those who delight in understanding science and sharing it with others.

The explorers may be the first to a topic, but the absorbers are the ones who make it understandable to the rest of us scientists.

References

- I wrote about this idea of the resources available to curious people dwindling as you go to the cutting-edge in a post for ErrantScience. I described the scientific literature as a “jungle”, and I still think this is quite apt.

- I won’t pretend I know all of the intricacies of peer review and its problems. But from what I’ve understood through reading other scientists, volunteering to review papers can take a lot of time that is not spent on building up your career. See this article by Jessica Borger (specifically, the section “Peer review relies on volunteers”) and this one by Tony Broccoli.

Endnotes