Precision in Language

I imagine that we do this all the time: you’re talking to someone else about solving a certain equation, and then you tell them something to the effect of, “I had to bring sigma to the other side of the equation.”

My question is: what mathematical operation did you just do?

On the one hand, we could be talking about bringing the sigma over to the other side of the equation by adding/subtracting a term on both sides of the equation. Alternatively, we could also be multiplying both sides of the equation in order to bring a sigma that was in the denominator to the numerator of the other side.

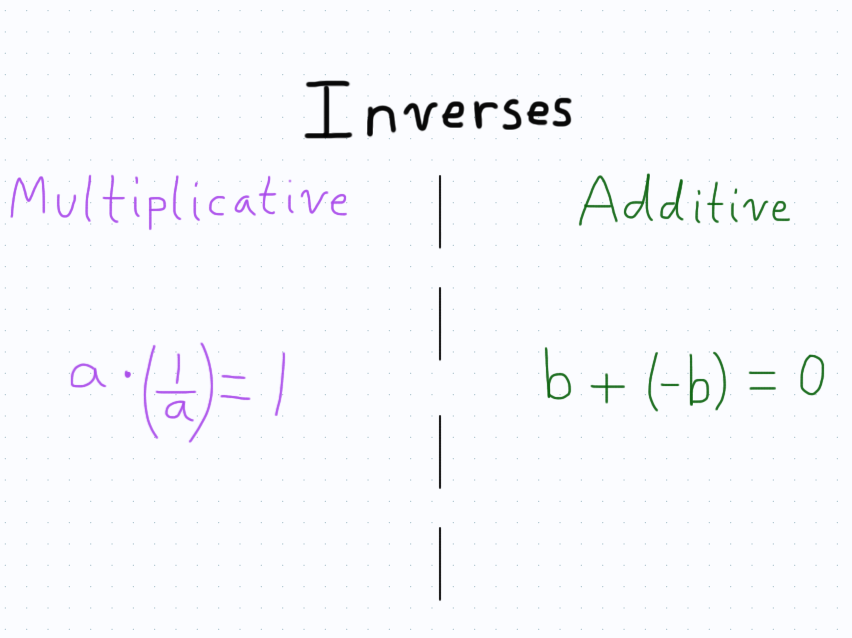

Both of these correspond to “bringing the sigma over to the other side.” However, we both know that these aren’t the same thing at all. In fact, you can make huge mistakes in a calculation if you mix up these two methods of bringing a quantity over to the other side of an equation. This happens because we have two notions of an inverse when doing arithmetic. We have an additive inverse, which simply means that when you add a quantity and its inverse, the result is zero. We then have a multiplicative inverse, which means when you multiply a quantity with its inverse, the result is one.

This is great, but the use of the language of “bringing” something over an equation buries this notion and creates the skill of what I like to call “equation gymnastics”. This is what happens when students don’t know how to manipulate equations and try to simply remember rules. You then see some people master the ability to solve equations simply by following the rules, rather than actually understanding.

Related to this is the notion of “cross-multiplying”.

Now, I don’t want to give the impression that there is no use to being able to blindly apply the rules of algebra. That’s not a problem, and it can make for students who are extremely capable of solving equations. However, from my experience, it is so much easier to tackle questions (particularly when they vary from the basic ones) when one understands why the rules are what they are. That’s the great thing about learning mathematics. The rules aren’t arbitrarily there to make one’s life difficult while solving equations. They are there because these rules are required if you want to balance an equation. This is the crucial point that I find is lost on students. All of these so called “rules” of algebra follow one main principle: an equation is a balancing act, and requires the same “things” on both sides in order to maintain equality. That’s it. All of algebra that one learns in secondary school can essentially be summed up into that one sentence.

However, I don’t think enough students are taught this. Instead, they stress out about remembering different methods of solving equations, or remembering that you need to “flip the sign” when you bring a term to the other side of an equation (but only if it’s addition or subtraction!), but that you don’t do this if it’s a term that is part of a multiplication or division. Phrased this way, even I start to wonder about these rules. When you think about equations in this light, everything seems arbitrary. But that’s not because the rules are arbitrary. It’s simply that you’re looking at the concept in a way that’s not as useful.

This isn’t limited to secondary students learning algebra. In fact, I face this problem all the time in my own learning. It’s not always a simple matter to find the “right” perspective on a concept that clicks for you, but I can guarantee that imprecise language does not help. When we use words like “bringing over” to talk about terms in an equation, we need to be sure that the people we are talking to know what we mean by that. If not, we should use more precise language to talk about what we are really doing when we say that we are bringing a term to the other side of an equation.

Personally, I try to avoid using the expression “bringing over” when I talk to the students I work with who are learning about algebra and solving equations. I’ve found that it’s simply not a good way to talk about equations, and so I’ve done my best to eliminate it from my vocabulary. My students might wonder why I use such a long-winded way to solve equations, but it’s because I want them to understand what they’re doing before they start developing their own shortcuts.