Proof that there exists a 3-regular graph for any graph with $k$ vertices, with $k \geq 4$ and $k$ even

Last time, we looked at some concepts in graph theory. In particular, we looked at the ideas of a simply connected graph, the degree of a particular vertex, what edges and vertices are, and some other related concepts. Here, I want to tackle a proof that has a nice way of visualizing the result.

Theorem: There exists a 3-regular graph for any simply connected graph with $k$ vertices where $k$ is even and $k \geq 4$.

To show this, remember that we have to show this statement holds for any even number of vertices that is greater or equal to four. As such, we could try and show this statement on a case by case basis, but it’s going to take a lot of time. In fact, it would take infinitely long, since we need to do it for every even number. We don’t want to do that, so we will have to come up with a better method.

This method is called induction.

If you want to get a quick primer on induction, you can read my post here. Briefly though, the idea of induction is to show that the base case holds, then to assume that the $k$ holds, and finally prove that the $k+1$ case holds. If you fulfil these requirements, then you’ve shown that the statement is true for all $n$ (in relation to your base case, of course).

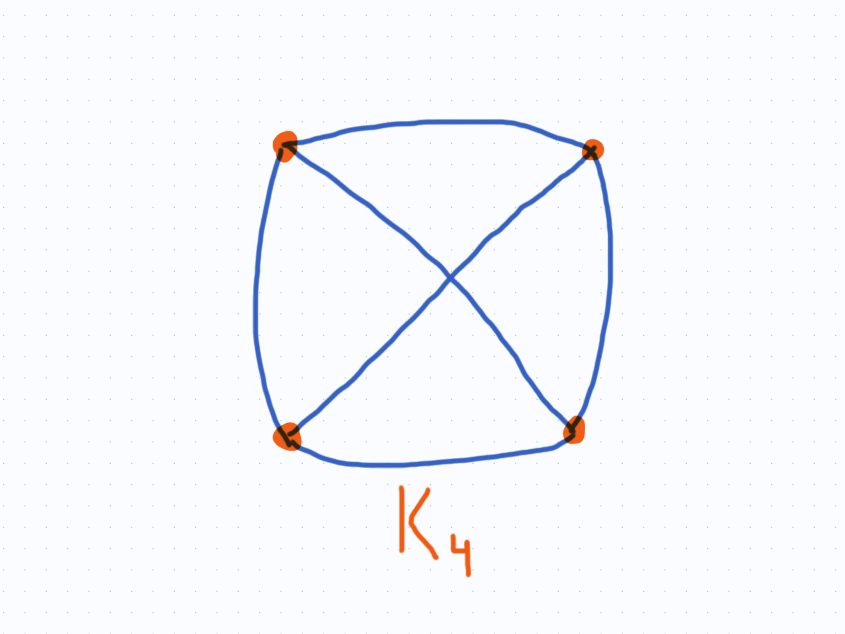

So let’s begin with our base case, which is when our graph has four vertices. Our goal is to construct a graph on four vertices that is 3-regular. In other words, we want each of the four vertices to have three edges that are incident with it. Furthermore, the graph is simply connected, so we don’t have any loops or parallel edges. After trying a few examples, you’ll quickly find that the only possibility is what we call the complete graph on four vertices, denoted $K_4$. This simply means that all of the vertices are connected to each other.

We now have to show that the case with $k$ vertices holds, and then check the $k+1$ case. However, I want to do something a little different, that will hopefully convince you that this theorem is true.

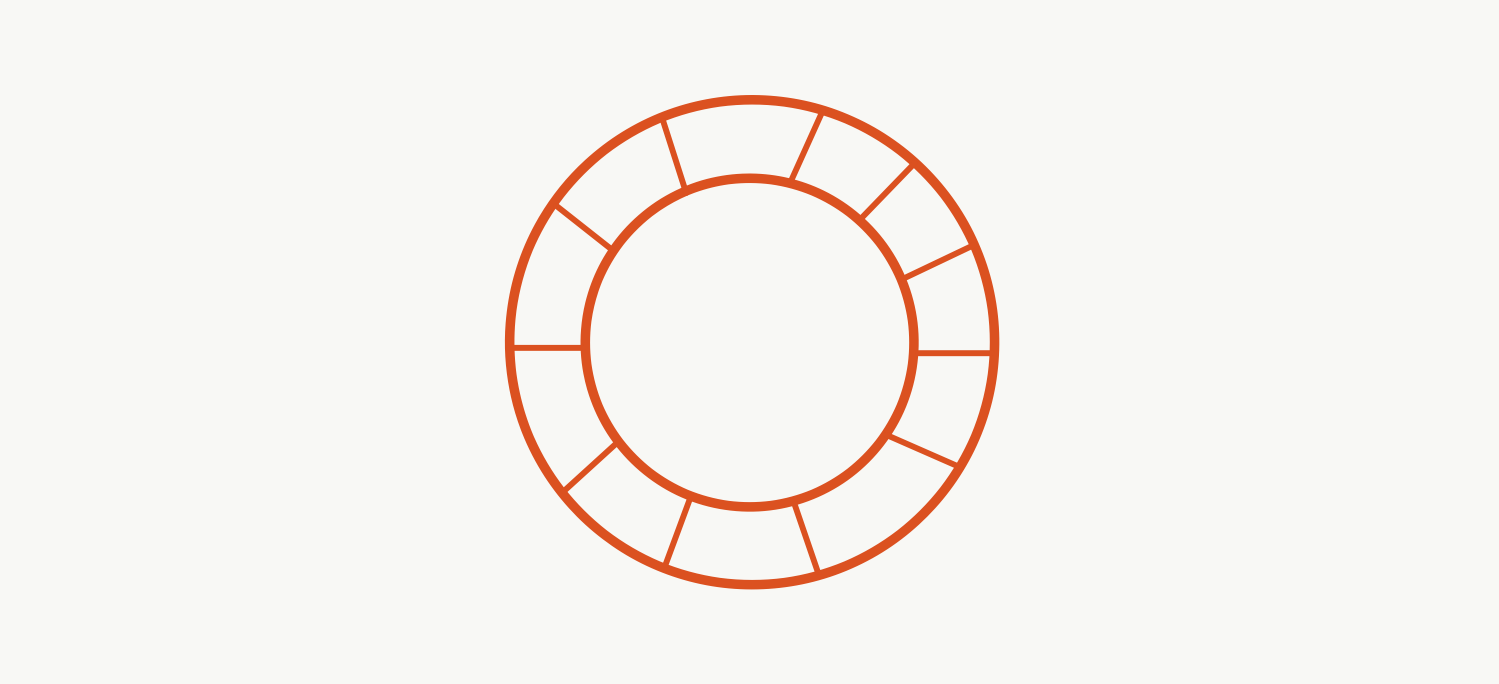

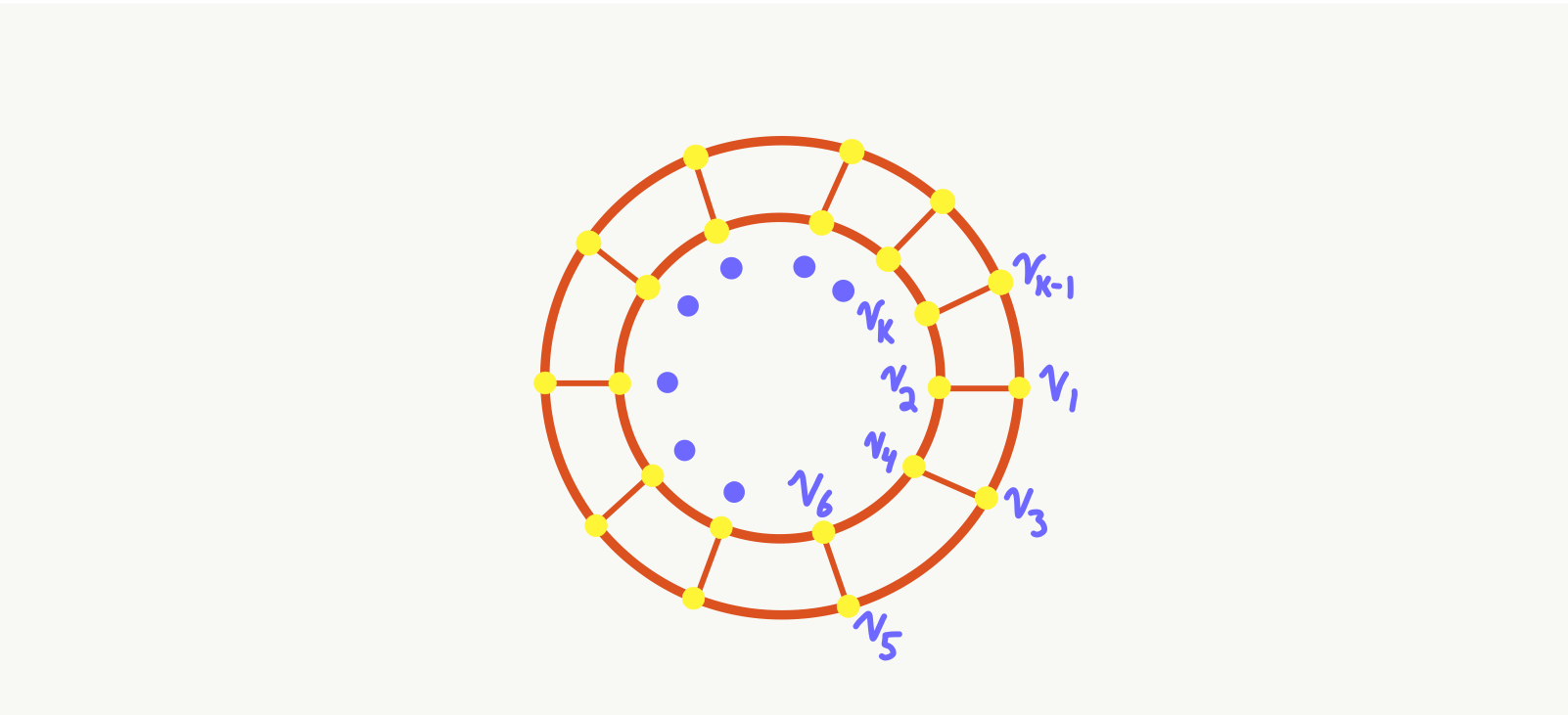

First, draw two concentric circles. Then, we want to connect the two circles by $\frac{k}{2}$ rays that go radially outward from the centre of the two circles. However, we only care about the segment of these rays that are between the two circles, so the sketch would look something like this:

Next, since we have $\frac{k}{2}$ line segments in our sketch, we will add vertices to every point that has the line segment intersecting a circle. Since each line segment intersects the circles at two places, we will have a total of $k$ vertices. Furthermore, you can look at any of the vertices to confirm that each one does indeed have three edges that are incident with it, and the graph is also simply connected.

And voilà! That’s our proof. If you look at the sketch, the reason why it’s important that $k$ be even is that we have to always add an extra line segment connecting the two circles, which means you’re adding two vertices. Then, as long as you keep on adding the two vertices like I’ve described, you can create a 3-regular graph for any even number of vertices.

Unfortunately, you can only use this nice sketch for $k \geq 6$. For $k=4$, the graph becomes one that has parallel edges, which is not allowed under our theorem. Therefore, we need to draw the graph $K_4$ for the base case. After that, we can go back to these circles to get the required other graphs.

Hopefully, this proof is convincing. I love visual proofs, and I think this one is particularly simple. It’s an easy inductive example, and it constructs the required 3-regular graphs with a simple algorithm.