Physics On A Cube

One of my favourite mathematical pieces of writing is Flatland, by Edwin Abbott Abbott (the book is in the public domain, so you can download it from Wikipedia). Published over a century ago, it’s a story involving residents (Flatlanders) who live in a two-dimensional world. Without giving too much of the story away (because you should seriously read it!), the inhabitants find themselves shocked when a strange shape dips into their world. That other “shape” is a sphere, which we know lives in a three-dimensional space. This confuses the residents to no end, and only a brave soul dares to push their mind further to explore the possibility of there being another dimension available.

What I take away from this tale is that there can be hidden dimensions available to us when we look more closely.

Okay, I’m not talking about the kind of extra dimensions from ideas like string theory. Instead, I’m referring to paradigm shifts that have occurred in physics, and how they carve out new dimensions in the space of possible theories for physicists to explore.

There is also a historical aspect to think about, since our theoretical frameworks for the universe have evolved along with our capability to actually probe the world. It’s difficult (or perhaps, too easy) to think about possible worlds when there are no constraints. There’s no feedback to guide you. That’s what experiments give us; ways of saying, “Okay, the world looks like this and not like that.”

Much like the Flatlanders, we began our story in a state of relative ignorance. The physics we knew (and learn as students) begins with Newtonian mechanics. This involves projectile motion, collisions, notions of energy, work, and momentum, and can be applied to all sorts of systems you would see in everyday life.

Here’s an example. If you see two things coming at each other, from the perspective of one of those things, the other is moving at the sum of the two speeds. This is the standard “addition” rule for velocities, and is something we grasp as kids playing sports. It’s also reinforced with every encounter we have, so it makes sense to assume that this is how the universe operates. Velocities add. Nice and simple.

But nature has some tricks up their sleeve. Namely, it is hiding the full story from us, just as the Flatlanders have no inkling of the third dimension.

In this case, there is more than one dimension. We will start with what captured the minds of many scientists in the 17th century, which is the study of gravitation and celestial mechanics. Here, the star of the show is Newton (with, like all advances in science, a slew of other characters that get a lot less limelight), but the specifics aren’t necessary. Instead, there was a problem. Celestial objects moved along the backdrop of the sky, and cannonballs rose and then fell back to Earth. There was all this motion, but how did it all work? Was there even any connection between these phenomena?

It was Newton who put forth his theory of universal gravitation, capturing everything into one compact equation (for the magnitude of the force):

Fg = G m1 m2 / r2.

Here, Fg is the gravitational force exerted by Object 1 on Object 2 (and vice versa), while m1 and m2 are the two masses and r is the distance of separation. For our story though, the important player is G, the universal gravitational constant. Now, if we wanted to talk about systems with some sort of gravitational nature, the constant G would be present.

This gave us a new dimension to think about. We started with looking at plain mechanics, and now we added gravity to the mix. Diagrammatically, we can illustrate our new space of frameworks as such:

Alright, so this is great. But like I said, this is far from the whole story. There were other surprises on the horizon, and would change how we view time and space.

Moving fast

Let’s think about our addition law for velocities again. In Newtonian mechanics, velocity vectors add in the usual way. This is done by defining something called an “inertial” frame, which is basically a way of setting up a coordinate system such that the system being analyzed is stationary, with everything else moving relative to it. To get an intuitive feel for this, just imagine being in a vehicle that is moving quickly. You know that you are the one moving relative to the trees. But if you let your mind relax, is it not equivalent to saying that the trees are rushing past you? This is what we mean by reference frames, and it was a huge help in analyzing systems using Newtonian mechanics.

There was a problem though. Not obvious at first, but cracks were beginning to show in physics. The main culprit was light. What would it look like to be in the rest frame (inertial frame) of a beam of light?

This is a question that Einstein pondered, and it led to his postulate that the speed of light was actually constant in all reference frames. Not only that, but this implied the the notion of space and time had to bend over to accommodate the fixed notion of the speed of light c.

Earlier in the history of physics, the speed of light was assumed to be infinite. In fact, it was only in 1676 that Ole Rømer gave convincing quantitative data that indicated the speed of light was finite. This set the stage for Einstein and his theory of special relativity. Space and time weren’t two separate things. They were intrinsically tied together through the speed of light to create spacetime. Furthermore, our notions of distance and time were dependent on our relative velocity with other systems.

But how could this be missed? Why didn’t we see any of these effects before? People certainly don’t move at the same speeds, so shouldn’t we have noticed relativistic effects?

This brings us to the new dimension that Einstein gave us for our space of theoretical frameworks. It turns out that the range of speeds we use as humans doesn’t really come close to unveiling relativistic effects. That’s because the key ratio is v/c (sometimes denoted β), where v is your speed relative to another system, and c is the speed of light. For most situations, this ratio is super-duper small. Small enough that equations such as the velocity addition law hold up. It’s only when we get to a very fast speed that relativity kicks in.

To picture this, a quantity that shows up in relativistic effects like time dilation and length contraction is the gamma factor, which is defined as γ = (1 - v^2^/c^2^)^-1/2^. If we plot this curve for various values of the speed v (and take units for which c = 1), we get the following plot.

I was even being generous with respect to the part I labeled as speeds that we inhabit. To give you a bit of perspective, the speed limit on the highways where I live is 100km/hr. If we express that in terms of the speed of light, the ratio is a huge 9.266×10^-8^. As you can imagine, this isn’t exactly easy to squeeze on my graph.

The key though is really that the speed of light c is finite. The exact value relative to the speeds we explore in our everyday lives would probably have affected how quickly we realized relativity was a thing, but the main idea is acknowledging that c isn’t infinite.

Because of this, our new dimension is an axis describing 1/c:

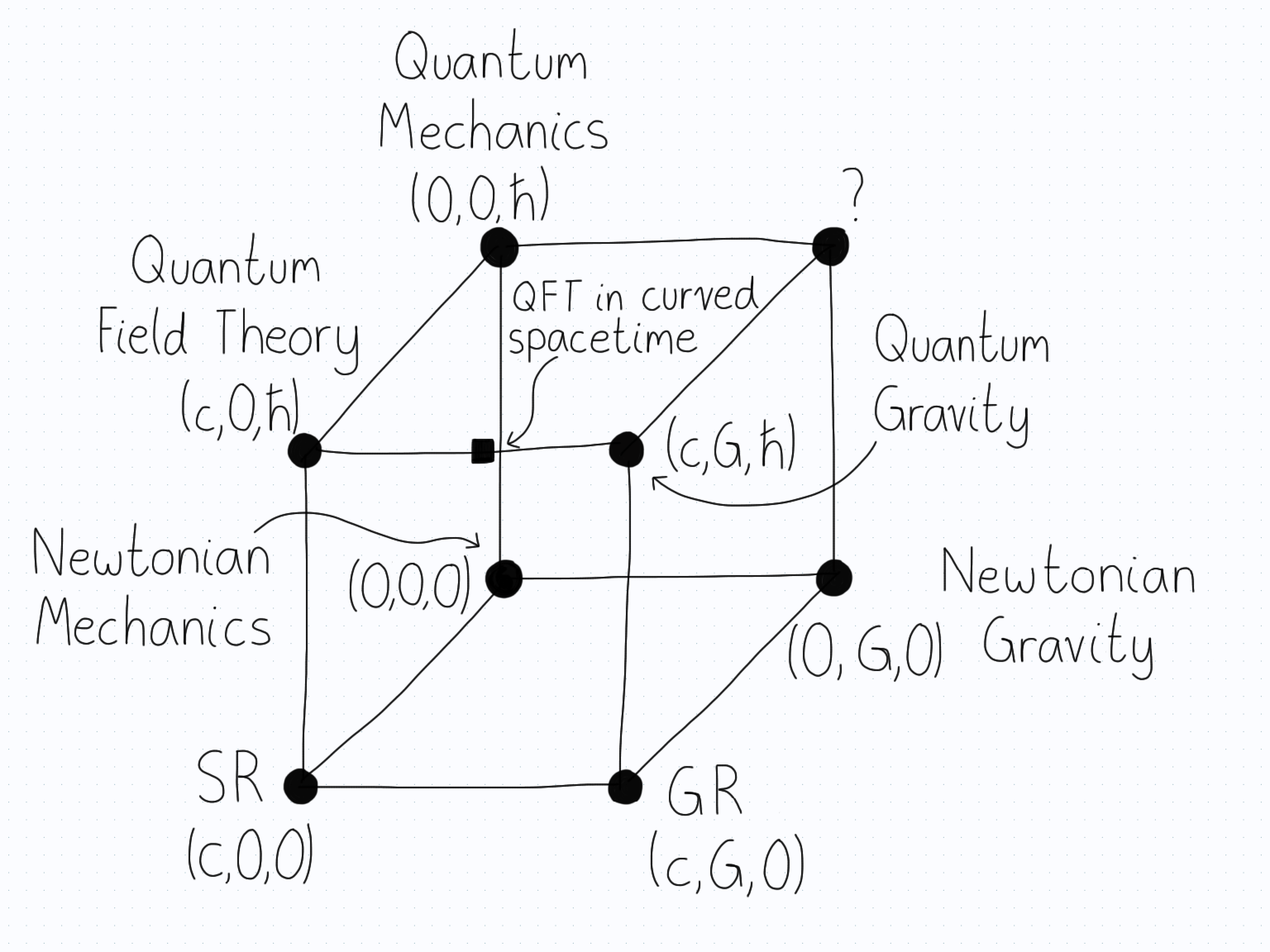

We now have two axes, each one with a “switch” we can flip. We can turn the gravitational constant G on or off, and we can do the same for 1/c. Note here that having 1/c = 0 implies that c → ∞. The origin (0,0) gives us Newtonian mechanics, (0,G) gives us Newtonian gravity, and (c,0) gives us Einstein’s special relativity.

But what happens when we switch on both gravity and special relativity? Well, that gives us the final corner of the square, which is general relativity. It occupies the coordinate (c,G), and finishes off our square.

So that’s great, and gives us two dimensions for physicists to explore frameworks. However, you can probably guess what we’re missing: the quantum.

Bring in ℏ

I did call this essay Physics on a Cube, so it’s probably not surprising that we have another dimension to add. This comes through the addition of quantum theory, one of our most sophisticated frameworks which was developed in large part throughout the 20th century. There’s a lot to say about quantum theory as well, but we’re just going to explore the vertices of the cube, so we’ll save in-depth explorations for another essay.

The reduced Planck constant ℏ is a very small quantity in units that we care about. As such, you might hear that quantum effects take place on the smallest levels of atoms, nothing close to the macroscopic scale of humans. While perhaps true, this hides the fact that quantum theory is the best description of the universe we have. And in principle, quantum effects could be seen on large scales, it’s just that quantum effects tend to be delicate, and so get washed out in our daily lives.

For our discussion though, the net result of discovering quantum effects is that our square of options becomes a cube. The new dimension corresponds to “turning on” the quantum effects by having ℏ move away from zero. Therefore, our space now looks like this (I’ve rotated the direction of some of the axes).

On the bottom, we have our original square. But now we can go up a level and make everything quantum. This gives us some new vertices to explore.

First, we have the vertex (0,0,ℏ), which describes the quantum theory physics students begin with: non-relativistic quantum mechanics. This is where you study the Schrödinger equation. No effects from relativity are added. What you usually study here are harmonic oscillators and a few simple “well” potentials. Even though we only have one framework “turned on”, there are still a bunch of phenomena that we get to explore. For example, this is where students learn about superpositions, tunneling, probability distributions, and much more.

Next, we can turn on relativity, which brings us to (c,0,ℏ). This is what happens when you take quantum mechanics and make it relativistic. Everything becomes a quantum field, and so the corresponding theory is called quantum field theory, or QFT. This is something I learned about during PSI, and it involves a lot of advanced mathematics and somewhat-sketchy-at-times prescriptions. I know there’s a lot of work being done in quantum field theory to give it a solid mathematical footing, and it seems to be where mathematical physicists often end up. I don’t have a ton to say about quantum field theory because I don’t had much experience working with it. Our best theories of physics are quantum field theories, and these encompass the Standard Model of particle physics, which is our theory for the zoo of particles that we know of in nature.

This vertex doesn’t include gravity, so the idea is that we are looking at quantum field theory in flat spacetime. That’s a fancy way of saying that our spacetime isn’t curved very much, so we can ignore gravitational effects as a good approximation. When you look at the mathematical guts of these theories, the Dirac equation and the formalism of an action principle pops up all over the place. These are sophisticated techniques that incorporate the invariance needed when dealing with relativity, which the Schrödinger equation doesn’t incorporate.

One other interesting thing to note is that there isn’t much being done to explore the (0,ℏ,G) vertex (the question mark on my diagram). From what I could find, this is kind of an ignored corner. This shows that the cube is more of a useful construct than something fundamental about reality.

It’s important to realize that this cube serves as a nice illustration, but you shouldn’t take it too seriously. There are some important questions that the cube leaves unanswered. As always, one of my favourite physics writers Sabine Hossenfelder wrote about the cube of theoretical physics almost a decade ago. I would definitely recommend looking at her post, since she gives some good critiques of this illustration. For example, can you “traverse” the cube in any way, or are there differences that accumulate? Also, are the choices of axes suitable for this kind of discussion? Reading her article will help answer those questions. I prefer to look at the cube as a way to hold information in my mind, rather than an actual manifestation of how the physical theories interconnect.

But now, we have one more corner to visit.

The far corner

It’s time to turn on all three frameworks: relativity, gravitation, and the quantum. Doing so brings us to (c,G,ℏ), the realm of quantum gravity.

Well, almost. First, it might be useful to talk about QFT in curved spacetimes. As the name suggests, we take QFT and go past using flat spacetimes. This might lead you to ask: Doesn’t this give us a theory of quantum gravity?

Not exactly. That’s because QFT in curved spacetime doesn’t incorporate all of the features of a dynamic spacetime. As such, I like to think of it as doing perturbation theory, where you take a theory you know and change it a little bit in order to get a more accurate description of your physical system. However, at the end of the day this is still not the full theory of quantum gravity. There are various reasons for this, but I won’t get into them for now. As such, you might think of QFT in curved spacetime as a marker along the edge to quantum gravity.

At the (c,G,ℏ) vertex, a full quantum theory of gravity emerges. At the time of writing this essay, no such theory exists. Physicists are working on ideas, but these are nothing close to being complete. As such, while we know this vertex is there, we don’t have any way to actually get there.

I find this to be a fascinating state of affairs. We have this corner to reach, but we don’t know how to get there because we don’t have the mathematical tools to move along the edges between the corresponding vertices.

This is worth repeating. Moving from one vertex to another isn’t a matter of just throwing in a new constant. There’s often a conceptual breakthrough (like Einstein with relativity and the existence of a maximum speed) as well as mathematical techniques used to move along the cube (like path integrals in quantum field theory). A question on my mind is then: What kind of new breakthrough will be needed for a theory of quantum gravity?

Before we get there though, there’s some unfinished business left for us with our cube.

Another dimension?

So far, we’ve talked about relativity, gravitation, and quantum theory. These are huge pillars within theoretical physics. But they aren’t the only ones. In fact, I’m sure that I’ve offended many physicists and students with this discussion, because I’ve left out one huge area of physics: statistical physics.

We could talk about the constant of interest being the Boltzmann constant kB, but that’s not what’s important here. Instead, when we look at statistical and condensed matter physics, what makes this field special?

The number of particles, N.

It’s not a fundamental constant like the others, but it is crucially important when studying physical systems. That’s because many systems in condensed matter exhibit emergence. You may have heard of emergence as the idea that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. In physics, the spirit is similar. Emergence means we get phenomena that only occur when enough particles have assembled together in the right state.

The classic example is that of a phase transition. The idea is that you have a bunch of particles (or degrees of freedom in your system), and there’s some parameter that controls how they behave, such as the temperature. Imagine moving that parameter along a slider, changing its value and looking at what the system does. For most small changes, the system will respond a bit, but nothing drastic will happen. However, sometimes this parameter will have one (or more) critical values, where sliding across that point will yield dramatic effects to the system you’re observing. For most physics students, this gets examined with the Ising model, which is a great conceptual tool for thinking about phase transitions, and one I hope to write about in a future essay.

So even though N isn’t a constant of nature, there’s still a very real sense in which the number of particles in your system matters. Furthermore, instead of thinking of N as the number of particles, it can be useful to think about it in terms of taking a continuum limit. This means that N represents the number of degrees of freedom in your system, and going to the large N limit implies that there are an infinite number of degrees of freedom.

The mathematical tool used here is called renormalization, a technique that lets us wrangle with potentially infinite degrees of freedom. To think about this, imagine you’re tallying the votes of a huge population. You could individually count the votes, but what you could also do is group people together. Then, each group gets a single vote which corresponds to the majority of the group. This would reduce the number of votes needed, and you could even do this over and over again at many levels, eventually making it much easier to tally the votes.

Renormalization is a fascinating subject, but for our purposes here it gives us a way to handle a large number of degrees of freedom.

If we add N to our dimensions, we would get a hypercube in four dimensions. I won’t draw it here because I’m running out of room to annotate things, but you can imagine it as another cube connected to the vertices of the existing one. Basically, you tack on another dimension index for all of the points and cycle through the combinations. For example, single-particle non-relativistic quantum mechanics would occupy the vertex (0,0,ℏ,1). Note here that, while the previous dimensions can be “on” or “off” (zero or one), for N, the more natural thing is looking at one particle or an infinite number of them (the continuum limit).

Now, a full theory of quantum gravity would also incorporate taking N to be very large. I won’t go into what the other vertices might mean, because I haven’t seen much on them anyway.

In the literature, this is known as the Bronstein cube, after the physicist Matvei Bronstein. Well, the cube is the one without N. When you include N, it becomes the Bronstein hypercube. The full theory of quantum gravity we are after then lies on the vertex where all of these dimensions are turned on.

Again, there are subtleties at play here that I haven’t treated in depth. Do all of these vertices make sense? Can you traverse the cube (or hypercube) in any way, or does the manner in which you traverse it matter? This is a tricky question of commutation of limits, which often is not as straightforward as we would like.

One aspect that seems clear to me is that going from a small number of degrees of freedom to a high one (low to high N) requires renormalization. By design, that “erases” some information. Thinkin about the voting example again. If the groups are made up of nine people and the two choices are 0 or 1, seeing a 1 at the group level just means there were at least five people who voted for a 1. How many people exactly remains a mystery. As such, I would speculate that taking the continuum limit is a one-way street.

Finally, there’s the possibility that something more is waiting for us to discover it. We might not know how to traverse the hypercube at the moment, but maybe there are directions we don’t yet know how to take. Of course, this is speculative in the extreme, but it also makes me hopeful. Even if physics is often seen as a reductionist science, finding a whole new dimension (framework of physical theories) would be exciting.

In the end though, I like to think of the cube of physics as a conceptual tool. In fact, when you have a bunch of binary options, organizing things along a cube makes a lot of sense. Much like it’s worth taking the time to organize your possessions so that they are easy to find, organizing the frameworks of theoretical physics helps me keep the main pillars ordered. I don’t want to take the cube too seriously. Instead, as Sabine Hossenfelder tells us, “All together, the “cube of theories” is a very appealing representation. But do not wonder if it confuses you – it has to be taken with a large grain of salt.”

Next month: The Curse of Dimensionality.

Endnotes

References

- For a nice introduction on the idea of phase transitions geared towards a general audience, see this recent Quanta Magazine article by Charlie Wood. You won’t get all the details of the system in question, but it does illustrate what a phase transition is.

- The Bronstein hypercube of quantum gravity by Danielle Oriti. arXiv:1803.02577. Section V starts talking about using N as another dimension for the hypercube.

- “The cube of physical theories”, by Sabine Hossenfelder. I would always recommend checking out her blog, Backreaction. It’s a compendium of useful scientific information with a no-nonsense attitude. I love her writing because she doesn’t shy away from pointing out when things are wrong or misleading.