Seamen hurry near the harbour, making final preparations for their vessel. They crunch through a blanket of red, orange, and yellow leaves. Their destination: Europe. A cool wind reminds them to keep working, anything to keep warm against the falling temperatures of autumn. It’s October 15th, 1657, and it’s departure day for the ship docked in the St. Lawrence River near Québec City.

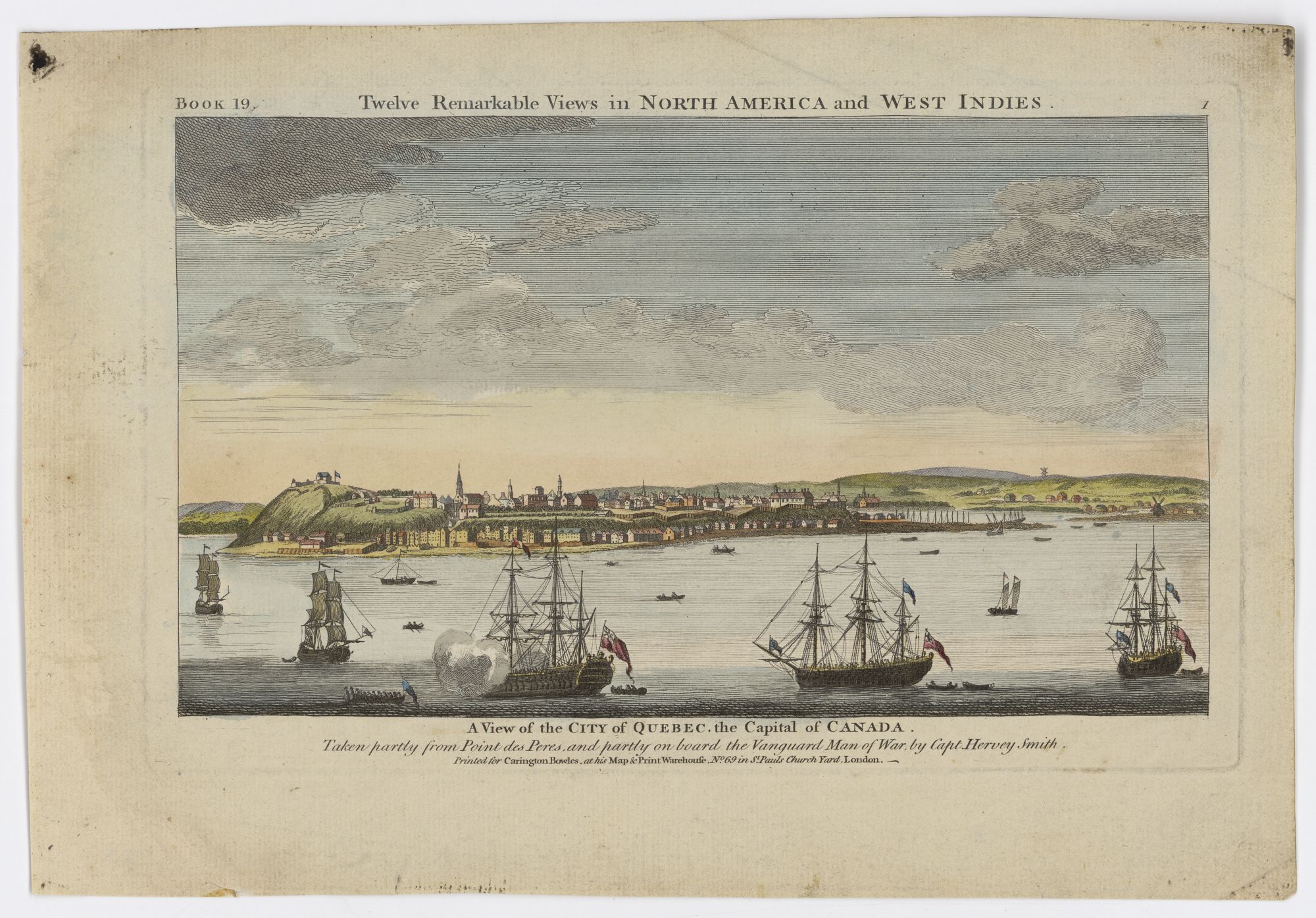

A view of Québec City around 1760, a hundred years later. Note the harbour and the small size of the settlement, even then. Created by Hervey Smith. Source

A view of Québec City around 1760, a hundred years later. Note the harbour and the small size of the settlement, even then. Created by Hervey Smith. Source

Today’s about more than just this ship, though. It’s the final outbound trip to Europe before the cold and ice arrive, making travel down the mouth of the river impossible. For the winter, the colonists in Québec City will have to be self-reliant.

Before they raise the anchor though, several colonists have approached the sailors, asking if they could carry their correspondence. This is their final chance to send any letters to their loved ones back in Europe.

One of these people is probably Marie Guyart, a founding member of the Ursuline convent here in Québec. As Jane E. Harrison recounts in the introduction of her PhD thesis (where I learned of this story), this is the final time Marie will be able to communicate with her son Claude before the ice closes her off from her homeland. After today’s letter, she will have to wait until the snow melts, the plants bloom, and the river thaws out before voyages begin anew.

The communication cadence between a colonist in Québec (New France) and a resident of Europe would be agonizing by our modern standards of email. “They’re taking _forever _to reply” wasn’t hyperbole but a fact of life. Remember: a voyage across the ocean took weeks or months, even during the summer. This delay increased the stakes of each letter, turning letter-writing into a sort of art form. There wasn’t any official postal service at the time to deliver mail throughout the colonies and Europe (though there were couriers and some individuals who would). Instead, people would often ask ships to carry their correspondence, perhaps paying them a small fee for the service. Postal organizations would only really begin in the 18th century.

Here in Québec, one big change occurred in the 18th century with the advent of a postal service connected to the burgeoning British colonies. As Harrison explains (page 2), people could continue writing through the winter by routing their letters south to New York, where ships could then leave for Europe. This development was progress in solidifying postal routes and a service throughout the colonies and enabling contact with Europe year-round. It was a slow process towards acceptance for people though, since they often could find others willing to do the job even more quickly. But over time, the postal services became the standard.

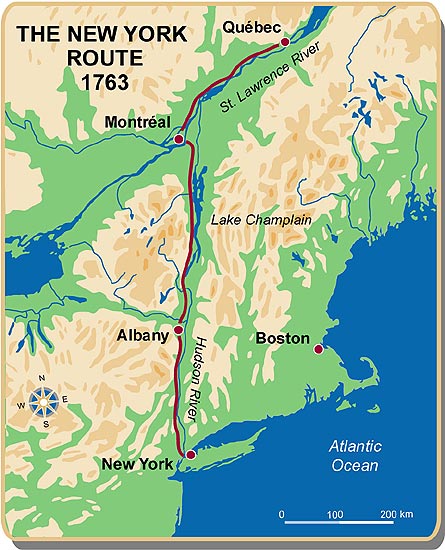

The route to New York. From the Canadian Museum of History (Andrée Héroux). Source

The route to New York. From the Canadian Museum of History (Andrée Héroux). Source

Steamships and railways helped propel the postal service into a faster and standardized system that people could rely on instead of entrusting their mail to random travelers (though there was still plenty of that). For example, when Canada ran its first railway line in 1836, delivery from Montréal to New York decreased by 5 hours (a 7% improvement). In my view, while technology was important, it was also important to establish regular shipping and railway routes that people could plan around. Communication delays decreased, increasing the connectivity of people who lived far away.

Still, correspondence is a far-cry from conversation. That’s fine if you’re placing an order. It’s less great if you want to keep in touch with a loved one who is far away. Electricity changed that. Over the last two centuries, humans invented and implemented the telegraph, the telephone, the radio, and finally the internet. Each one required time and effort to establish the infrastructure, but we gained enormous connectivity with people far away from us. These inventions also expanded our range of possibilities. The telegraph accelerated the post. The telephone and radio accelerated delivery of our voice. And the internet opened up the possibility for real-time video calls.

These days, I don’t think of physical space as a barrier to communication. I have friends who I’ve literally never met in the physical world. I’ve talked, laughed, and built relationships with them online, all because of our ability to harness the speed of light for our communication infrastructure. There are downsides to such a culture, but connecting with friends isn’t one of them.

If we take a broad view of history, we’ve increased our potential for sending messages across vast distances in a timely manner. Not all of the world is connected to the same degree, but most regions are more connected than they were in the past. What once could be a perilous journey across the ocean to deliver a message from a colonist in New France to Europe is now just a few taps and seconds away. This can create the illusion that connectivity is only an implementation issue since the speed of light is effectively instantaneous relative to distances on our planet.

Looking to a (hopefully not-so-distant) future in which we settle on other planets, how hard could expanding our communication network to encompass them really be?

The answer: very hard. The problem is that space is big. No, I mean really big. Just traveling to the nearest star at light speed would take over four years (and by the end, you would curse the laws of physics for such a sluggish cosmic speed limit). If we want to become a multi-world species, I wonder how the speed of light will fracture our conversations with loved ones during a trip, our calls back home when we move to new worlds, and our cadence of receiving news from other planets.

Many of us are used to hopping on a call with another person, talking in real-time. But we won’t be able to do that if we’re trying to contact someone on another planet or far-away station. It takes around twenty minutes for a light signal to travel from Earth to Mars, over half an hour for Jupiter, and over an hour for Saturn. And we’re still talking about the solar system here!

Distance is proportional to the time delay, but my enjoyment of a conversation is not. Anything up to a few seconds of delay is annoying but manageable. Ten seconds, though? I don’t think I’m going to want to have many of those exchanges. Electricity once bridged distant locations to turn correspondence into conversation, but becoming a multi-planetary civilization might force us back to a slower mode of conversation.

Imagine a young engineer traveling to Mars to begin her career. For the first few days, conversations with her parents remind her of just having a very laggy internet connection. After a week, they’re interrupting each other all the time due to roughly a five-second delay. After two weeks, she and her parents learn to pause for several awkward moments each time one of them speaks. After a month, the engineer begins reading a book while she waits for her parents’ reactions, nearly half a minute late. By the second month, she tells her parents they should simply start exchanging video messages.

Unless we’re communicating with nearby worlds, I suspect we will revert back to the cadence of email and letters, where we don’t expect a reply any time soon. That means no video calls, no online courses with synchronous sessions, and a lot more recorded video messages (or even just text).

I also wonder if it will make our worlds more isolated. After all, if I can only communicate with you through a delay, will I want to put in the effort to do so? Maybe, but I’d probably rather make friends with those on nearby worlds with a bearable time delay. Perhaps sending long-form messages with lengthy time delays will become an art form like it did for the colonists in New France. Or maybe we’ll all become experts at using asynchronous tools like remote workers currently use.

For official communication from organizations such as governments, I’m unsure what will happen. My guess would be that organizations will focus their scope around worlds they can rapidly communicate with. After all, you don’t want to wait on a reply for a time-sensitive issue because the head office of your judicial system is light years away.

The common theme: Our experience of time will probably limit the practical sphere of connectivity.

We’ve done really well at pushing our communication infrastructure to the limits of the laws of physics. Saturating them allowed us to temporarily convert correspondence into conversation. But when it comes to increasing connectivity in an expanding civilization, space always wins.

Note: I took some liberties in painting the scene surrounding October 15, 1657. However, the date and departure of the vessel do match the records. I learned of this fascinating account from Jane E. Harrison’s PhD thesis, “An Intercourse of Letters: Transatlantic correspondence in early Canada, 1640-1812”.

Thank you to Malcolm Cochran, Rob Tracinski, Heike Larson, and Camilo Moreno-Salamanca for feedback on earlier drafts.

Endnotes

Each winter, I set a goal of not slipping on ice during my runs. Each winter, I’ve failed. Bruised hips and scraped knees tell those tales. Darkness is the primary factor. A typical run begins long before there’s even a hint of morning light. My steps are never fully confident, the snow concealing potential danger on the road.

Step here, step there.

Keep my feet light.

Slow down before turning.

Watch out for snow-filled potholes.

It’s part muscle memory, part good intuition, part reflexes, and part guessing game. A small relief: On my most frequent road for dark winter running, the 9 lampposts emit bubbles of illumination. They reassure my steps, if only briefly. But near the end of the cul-de-sac lies a stretch where there are no more bubbles and it’s just me with the darkness.

This year I have hope though: My town installed an extra lamppost, providing one last bubble of light. Perhaps this year will be the year I succeed.

Either way, I soon won’t even notice the lamppost as being “new”. In a few years, I may not even remember that there was a time without its light. But it will make me safer.

That’s the nature of infrastructure: when operational, it’s an invisible supporting actor in our lives. It’s unassuming, quietly working in the background to enable everything else in my life. Imagine if I had to manually turn on my lampposts, or send a request to my town to activate these particular lights at a certain time! It’s absurd, which is why infrastructure functions best when it’s invisible.

In fact, it’s when things go very wrong—a natural disaster, a human accident, or a tipping point in a system—that we sadly remember. Infrastructure failures expose the concealed wiring of our civilization.

Amidst the deluge of useless emails came a gem that made my day.

It was December 30, 2020, in that liminal week where everything seems to stand still as we transition from one year to the next. I was in my own transition period. After completing an unorthodox master’s degree in theoretical physics, I was now a fresh PhD student trying to integrate myself in a new research group and university.

In fact, the email concerned this master’s program. It was from an undergraduate student, and it was remarkable for three reasons. First, she had enjoyed an essay I wrote about my experience in the program (when essentially the only other personal experience online was from a decade-old blog post). Second, she had also seen and loved my webcomic. And third, I had no idea who she was, which meant they had literally reached out from the goodness of her heart.

This email kicked off an exchange with the student, and I was fortunate to play a part in helping her apply and join the program. All because she did more than just read my work. She reached out.

In writing this essay, I went back and read the email. It still brings a smile to my face! Having someone take the time to write and say they enjoyed my work is such a nice feeling. It validates that I’m on the right path, doing work that matters to others, and not shouting in the void. Believe me: the usual response to my work is radio silence.

And yet, I didn’t reach out to creators as often as I could. My default was to read an article or book, take about three seconds to contemplate it, and then move on to the next thing. It’s easier to read something new than to switch contexts, find a way to contact someone, and compose a note. Each task added extra friction, nudging me away from acting until it became a habit. I was as guilty as anyone of doing this, despite knowing how lovely it is to receive a kind word from others.

As a writer and artist, I can tell you: It means so much to get a nice note from someone that says your work moved them. And for the 99% of us who aren’t so famous that we’re inundated in emails, I suspect most would be glad to hear from you. I like email because it’s personal, but commenting on their site or mentioning them on social media can also work. Who knows, you may even forge a connection with the artist that turns you from a passive reader to an active fan.

I know I did. I’m a huge fan of the mathematician Jim Propp’s monthly essays. One month, I decided to go beyond reading. I reached out, thanked him for his work, and offered to give feedback on his early drafts. I’ve done so many times since. I became an active fan, and that wouldn’t have been possible without sending an email.

Now, I fight back against my impulse to simply move on. If I come across a piece I really like, I write the creator a quick email. Nothing fancy, just a heartfelt message that expresses what I like about their work. My favourite part is hearing back from the artist who is usually so appreciative that I took the time to reach out. I try to do this a few times a week because it’s a kindness that costs me so little yet provides the artist so much.

For a medium we often associate with busywork and drudgery, email also offers us an opportunity. Whose day will you make by sending a note of appreciation?

Thank you to Jennifer Morales, Jeff Giesea, Robert Tracinski, Becky Isjwara, Sarah Khan, Michaela Kerem, Tina Marsh Dalton, and Alex Telford for feedback on my initial draft.